Three Essays in Winter

I.

When I was a young man studying literature at the University of South Florida, I was always searching for activism in the books I read. It made me a terrible scholar, but it sharpened my view of social justice.

I dreamed of being a writer, thinking I could learn by studying the greats. Instead, literature showed me the problems of every age. Through Dickens, the tensions of the French Revolution; through Kerouac, the disaffection of post-war America. Ellison laid bare the pervasiveness of racism, and Plath, the crushing weight of patriarchy.

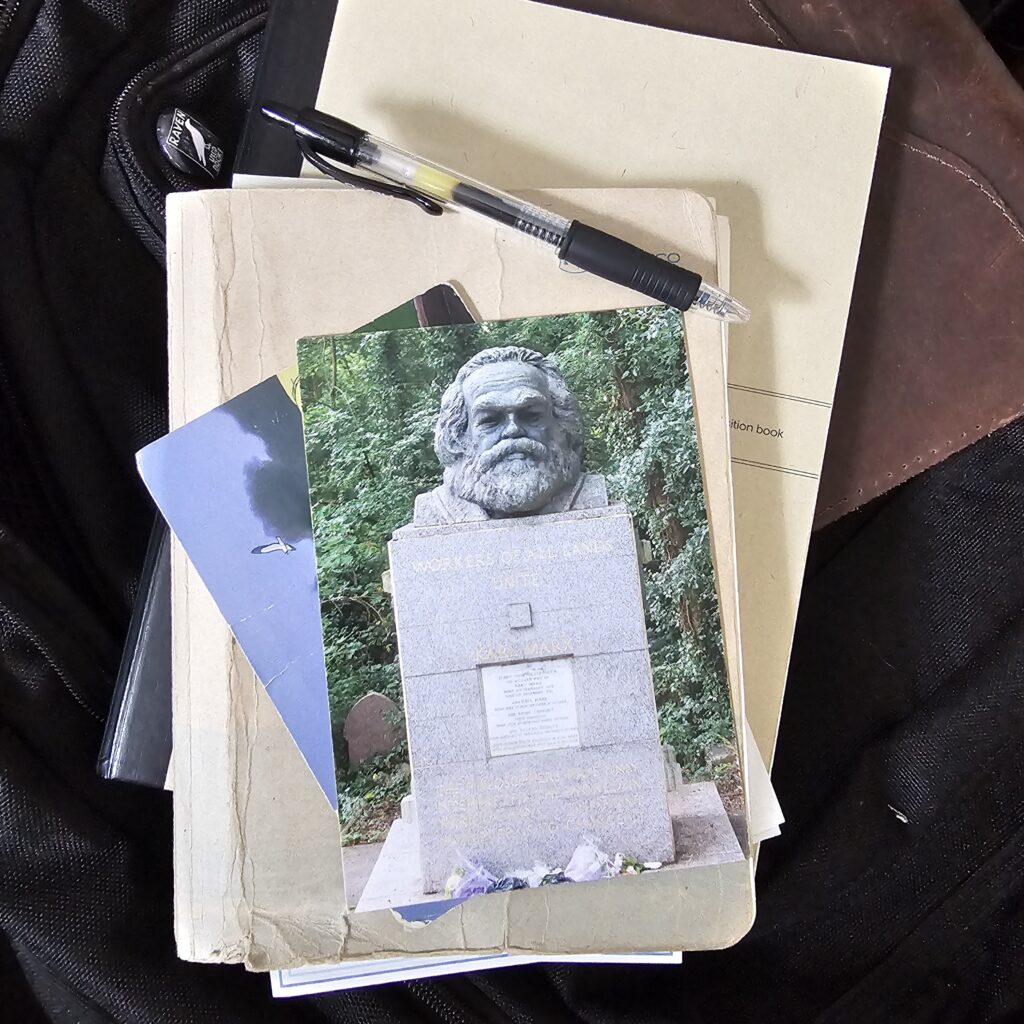

By my final year, I discovered Adorno and Horkheimer, and soon Marx, Lenin, and Bakunin. The Frankfurt School taught me power and culture are inseparable, while Marx and Bakunin showed me the urgency of action. By graduation, I was no closer to being a writer, but I could describe every problem in the world.

Literature in this way led me to activism, where I hoped to turn its lessons into action. For fifteen years, I chased justice, first in the streets as a community organizer, and now in the courts as an attorney. Over time, I have come to understand a truth I had missed in my classes: words hold the power to transform reality, ignite movements, and change the world.

Now I have come full circle, for it is activism that has led me back to literature. Protest chants, petitions written in fury, and legal pleadings that break the chains of incarceration—have revealed to me the power of language and the purpose of literature.

Every thought and action we take is mediated by words. Out of language, we conjure the world, and this conjuring creates action. Hope, belief, and doubt are shaped by language, limited only by our imaginations.

The courage to change the world begins with using words that spark action, as action always comes from words that measure our belief in possibility—whether of justice, or in ourselves.

If all our days are pages, what words will you write? Will they echo the past, or speak in a voice entirely your own? If change begins with words, where will you begin?

II.

I stood under the Prison Ship Martyrs’ Monument among the diamond encrusted ice of the stone platform, and I heard the prisoners’ cries, choking in the stifling hot air of the jails.

The largest and first battle of the Revolutionary War was fought here, in the hills of Brooklyn. Perhaps the first battle of the next Revolution will be fought here, as well.

Some 250 years have come and gone since those Continental Army volunteers, doomed in the damp prison ships, perished. Yet the Republic for which they stood, has continued to live.

When the first skirmishes of the war broke out, victory was a distant dream, and the Republic itself, an unshaped notion, yet hundreds of militiamen died in the very first hours.

Soon, through genocide, the conquest of indigenous Native Americans, the slavery of Black people, and disenfranchisement of many, the Republic spanned coast to coast.

Now, this Republic, which derives all of its legal and political power and sovereignty from the people, and the land upon which it stands, we are told, is incapable of fitting the people.

The Declaration of Independence, for which the ship martyrs perished, declared of government: “it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it.” The Power is with the People.

Yes, this land can fit you and me. It can fit every religion, it can fit every race. It can fit every political persuasion, even the deranged fascist, or the idealistic socialist like myself.

Even so-called ‘illegal aliens.’ Whatever label they are given, I call them them one of us. It fits our gay and trans loved ones. And your friend with the over-sized truck.

Despite how flawed our founders were, the prison ship martyrs died of hunger and despair for these principles, they died so you could wear the flag, or desecrate it if you chose.

This land does not belong to political parties or corporations, it belongs to those who are prepared to build the Republic, by and for the people. This land belongs to you and me.

I sat with these words flashing through my mind, as the sky turned black above the flaming torch of the prisoner monument. I put on my cap, and with the ghosts of the martyrs, departed.

III.

A time came in winter, when I sat by the East River on the edge of Brooklyn, watching the frigid waters, and waiting for death.

Since childhood, I have had bouts of paralyzing Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. As a boy, I would wear lotion filled gloves at night to mend the skin of my hands, torn apart from compulsive washing.

This malady has manifested in many ways. At times, for weeks on end, the front door has seemed to me nothing but a passageway between life and death, which I dared not cross.

To go out in the height of these bouts felt like certain death, but a day came when out of exhaustion, I was ready to die, and I decided to go in search of it.

I walked past the barren trees of Brooklyn, stopping every few blocks, scared to leave life behind, scared of every passerby and shadow, but I pressed on, determined to meet my fate.

When I finally came to my favorite bench on the water, where I was sure death awaited, I sat down, waiting for something or someone that I knew was sure to kill me.

Hours passed. Nothing or nobody came, and it seemed that despite my fears, it was not my day to die. Reflecting on this, my eyes fell upon the remnants of a nearby broken bottle.

I stood and went to stomp on the bottle to celebrate my marriage to life. I brought my foot down—and missed. I turned back to the river, and I looked upon the city that had given me so much.

What could I bond my soul with, what could I trust my life with, that had always been there, that would care for me and I for it with complete abandon, for the rest of my days?

I turned from the river and back to the bottle. “From this day forward,” I said aloud, “I am married to the pen.” I steadied myself with a handrail, raised my foot, and drove my heel into the glass.

I stood there, frozen for a moment in a cloud of glittering glass. The Earth beneath me shook. I felt a strength that I had never felt. Now that I had the pen, not even death could touch me.

The sun broke. I could hear the birds singing in the branches, and I saw the gold-tipped waves. In order to grow, we must always leave something behind. I turned without looking back, and I left my fear with the glass, ground into dust.